*Corresponding Author:

Girolamo Pelaia,

Department of Health Sciences, Magna Græcia University, Catanzaro, Italy

Tel: +39 09613647171

Email: pelaia@unicz.it

Abstract

Whenever an adequate diagnostic material is available, Rapid On-Site Evaluation (ROSE) has proven to be an important, easy and cost-effective adjunct in the diagnosis of thoracic lesions, so that for example cytology may even outperform histology in diagnosis of lung cancer. Our team applied ROSE on a sample obtained through Trans-Bronchial Needle Aspiration (TBNA), which can be useful for diagnosis of thoracic metastasis. In the present case report the primitive tumor was a polypoid melanoma, which had been excised in 2013. We performed ROSE coupled with TBNA without the support of Endobronchial Ultrasound (EBUS), thus succeeding in confirming the diagnosis of polypoid melanoma metastasis, suspected on the basis of patient medical history. ROSE is a diagnostic procedure that allows considerable time and cost savings when the sample is collected, prepared, observed and interpreted by expert operators. Indeed, we noticed a very reliable morphological consistency between the primitive histological lesion and the metastatic cells found in the sample aspirated from a mediastinal lymph node.

Keywords

Polypoid melanoma; ROSE; TBNA; Thoracic metastasis

Introduction

Polypoid melanoma, which is considered to be the most malignant form of this tumor, is a variant of nodular pattern. Melanoma cells accumulate in large amounts on skin surface, thereby promoting dislodgment of tumor cells that are carried to superficial lymphatic vessels, without invading reticular dermis; this feature differentiates polypoid melanoma from the non polypoid nodular variant [1]. When compared with the latter cancer phenotype, polypoid melanoma results to be associated with a greater lesion thickness, more frequent ulceration, younger patient age, and higher probability of occult metastasis. Polypoid melanomas are often located in the trunk, but also unusual sites such as nasal mucosa, hard palate and anorectal junction are known. The 5-year survival rates for patients with polypoid variant, non polypoid nodular pattern, and superficially spreading melanomas are 42%, 57%, and 77%, respectively. It is possible that the poor prognosis of polypoid melanoma is due to the deepest penetration of cancer tissue at the time of surgical excision [2].

Case description

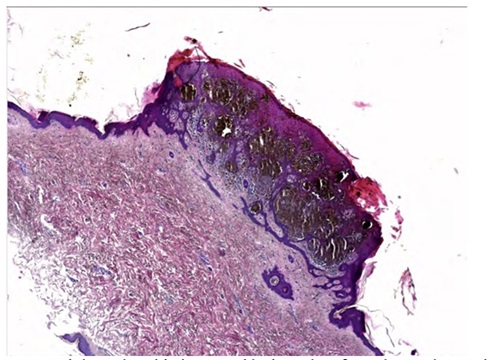

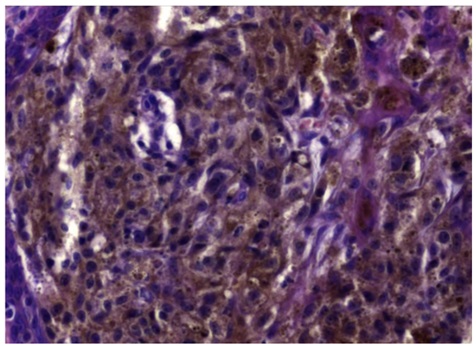

Here we describe the case of a 57-year-old white man, never smoker, referring to our University Hospital Respiratory Unit (Catanzaro, Italy) because he complained of irritative cough not associated with sputum. Remote pathological history was characterized by the occurrence of a polypoid melanoma excised in 2013 from the trunk, staged IB. Through an accurate in-depth search within our histopathology archive, we found the histological preparation regarding the polypoid melanoma excised in 2013 from the trunk (Figures 1 and 2). It was an atypical polypoid nodular melanocytic lesion, with no apparent vertical growth, and with a pagetoid, focally ulcerated growth pattern. The lesion was rich in melanin pigment. Mitotic figures between 1 and 6 were present. There was no intra-tumoral lymphoid infiltrate. Excision margins were large and free from tumor invasion. No sentinel lymph node was detected at that time. There was no evidence of vascular and perineural invasion in the sections under examination.

Figure 1: Nodular polypoid pigmented lesion taken from the trunk, consist- ing of atypical melanocytes, with pagetoid spreading. Wide and free exci- sion margins. Absence of necrosis, focal ulceration. E.E. 2.5 X

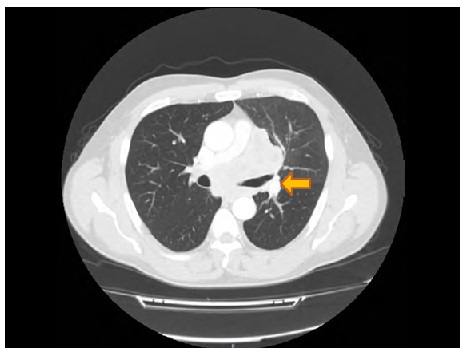

The last annual follow-up CT scan, performed during May 2019, showed the presence of an inhomogeneous 9 cm-sized opacity of probable lymphoid origin, embracing the main left bronchus and extending up to the middle third of the esophagus, from which it did not appear to be dissociable (Figure 3). This radiologic lesion was distributed as a sleeve also involving the emersion of pulmonary arteries and veins, which however did not seem to be infiltrated; vascular pulmonary trunk was reduced. Other alterations were also evident, including three lingular nodules, splenic hypodense formations, a left adrenal pseudonodular lesion, and three diaphragmatic noduli.

Figure 2: Higher Magnification of figure 1 shows prominent nucleoti and abundant powdery melanin pigment. E.E. 40X

Figure 3: CT scan shows a 9 cm-sized opacity of lymphoid origin, which envelopes and compresses the main left bronchus. The arrow indicates the lesion.

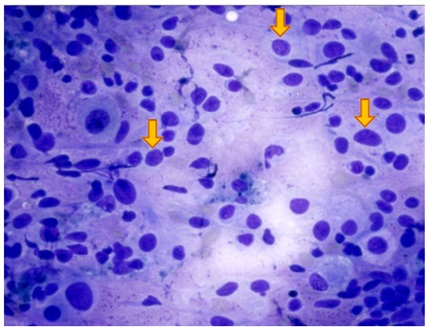

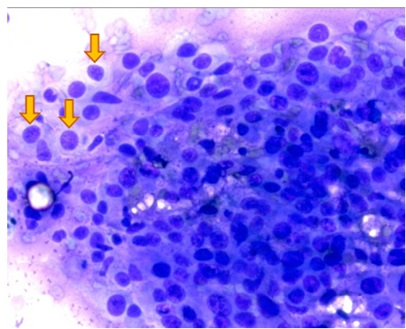

Our patient underwent flexible bronchoscopy (bronchoscope EB-580T 2.8, FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan-Figure 4), which showed a gross extrinsic compression of the left upper lobe, associated with congestion and hyperaemia of bronchial mucosa. TBNA without EBUS was practiced on the subcarinal lymph node station (VII) for cytological examination. Through this procedure we got a sample which was stained by diff quick method. Careful visual analysis made it possible to detect epithelial-like cells, mostly displaying individual cellular patterns featured by voluminous and pronounced nucleoli, as well as by powdery cytoplasmic pigmentations (Figures 5 and 6).

Discussion

CT scan surveillance has a high potential value in patients at high risk for systemic relapse of malignant melanoma. Thorax is a preferred site for early detection of surgically resectable metastases, potentially associated with longer patient survival [3]. With regard to the risk of development of thoracic metastases, univariate predictors can be considered such as male sex, black race, marked primary thickness (millimeters), higher Clark’s level, nodular or acral lentiginous histology, and location in trunk, head, or neck, as well as positivity for metastasis of regional lymph nodes [4]. Although our patient is a white male, his primitive tumor was located in trunk and was characterized by a very aggressive histological phenotype. Even if excision margins were unscathed and the search for sentinel node was negative, a close follow-up was indicated and proven to be useful [5]. Furthermore, we should also consider that several molecular alterations associated with melanoma have been successfully discovered [6-8]. In particular, whole-genome sequencing studies performed on patients with primary and metastatic melanoma have made it possible to detect distinct molecular subtypes on the basis of mutations involving many gene families including BRAF, NRAS, and NF1 [7]. A further subtype has also been identified and named “triple wild-type” because is characterized by a lack of hot-spot BRAF, RAS, or NF1 mutations [8].

Figure 4: Flexible bronchoscope EB-580T 2.8, FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan.

Figure 5: Cytological preparation provided by means of ROSE technique, and colored with Quick Stain. Pleomorphic and epitheliomorphic cells are visible, characterized by an inverted cytoplasm/nucleus ratio, a voluminous nucleolus, and scattered pigmented cells including powdered melanin gran- ules (indicated by arrows). These cells are visible in non-cohesive clusters.Q.S. 40 X

ROSE can ensure that the targeted lesion has been effectively sampled, and can also minimize the need for repeated diagnostic procedures aimed to perform additional investigations such as molecular studies [9]. Therefore, ROSE may be useful in reducing the number of aspirations, as well as in decreasing the total procedure time of TBNA and the rate of post-procedure complications. ROSE is also helpful in providing a preliminary diagnosis which can lower the number of additional invasive procedures such as mediastinoscopy [10]. Despite the relevant importance concerning biomarker detection and molecular profile, we have postponed these analyses because they had already been carried out on the primitive trunk tumor. Hence, TBNA coupled with ROSE allows deferring additional biopsies thus lowering procedural risk, without suffering any loss of diagnostic yield, and making also possible to concomitantly improve cost effectiveness [11]. With regard to our patient, a strategic approach based on the use of TBNA and ROSE has been successful to formulate a correct diagnosis, which did not require the support of either EBUS or mediastinoscopy.

Figure 6: Common morphological aspects shared by cellular patterns characterizing the primitive melanoma lesion and the metastatic sample aspirated from mediastinal lymph node (melanin granules are indicated by arrows). Q.S. 40 X

Conclusion

In conclusion, we performed ROSE on TBNA without EBUS support, thereby succeeding in confirming the diagnosis of thoracic metastasis of polypoid melanoma suspected on the basis of medical history collection. Therefore, this diagnostic procedure can be very useful when the sample is obtained, prepared, and interpreted by expert operators. Moreover, the combination of TBNA and ROSE can also result to be considerably time-and cost-sparing. The key diagnostic platform underpinning this case report refers to TBNA/ ROSE-dependent detection of a metastatic lesion of polypoid melanoma, located in a mediastinal lymph node and characterized by a histopathological pattern that consistently reproduced the features of the primitive trunk tumor.

Disclosure Statement

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1. Plotnik H, Rachmaninoff N, VandenBerg HJ Jr (1990) Polypoid melanoma: A virulent variant of nodular Report of three cases and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol 23: 880-884.

- 2. Manci EA, Balch CM, Murad TM, Soong SJ (1981) Polypoid melanoma, a virulent variant of the nodular growth pattern. Am J Clin Pathol 75: 810-815.

- 3. Gromet MA, Ominsky SH, Epstein WL, Blois MS (1979) The thorax as the initial site for systemic relapse in malignant melanoma: A prospective survey of 324 patients. Cancer 44: 776-784.

- 4. Harpole DH Jr, Johnson CM, Wolfe WG, George SL, Seigler HF (1992) Analysis of 945 cases of pulmonary metastatic J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 103: 743-748.

- 5. Ascierto PA, Agarwala S, Botti G, Cesano A, Ciliberto G, et al. (2016) Future perspectives in melanoma research: Meeting report from the “Melanoma Bridge”. Napoli, December 1st-4th J Transl Med 14: 313.

- 6. Rabbie R, Ferguson P, Molina-Aguilar C, Adams DJ, Robles-Espinoza CD, et al. (2014) Melanoma subtypes: Genomic profiles, prognostic molecular markers and therapeutic J Pathol 247: 539-551.

- 7. Greenhaw BN, Covington KR, Kurley SJ, Yeniay Y, Cao NA, et al.(2020) Molecular risk prediction in cutaneous melanoma: A meta-analysis of the 31-gene expression profile prognostic test in 1,479 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 83: 745-753.

- 8. The Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2015) Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell 161: 1681-1696.

- 9. Chandra S, Chandra H, Sindhwani G (2014) Role of rapid on-site evaluation with cyto-histopathological correlation in diagnosis of lung lesion. J Cytol 31: 189-193.

- 10. Jain D, Allen TC, Aisner DL, Beasley MB (2018) Rapid on-site evaluation of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspirations for the diagnosis of lung cancer: A perspective from members of the Pulmonary Pathology Arch Pathol Lab Med 142:253-262.

- 11. Baram D, Garcia RB, Richman PS (2005) Impact of rapid on-site cytologic evaluation during transbronchial needle aspiration. Chest 128: 869-875.

Citation:Lio E, Pelaia C, Gaudio A, Marrazzo G, Pelaia G (2020) Utility of Endoscopic Trans-Bronchial Needle Aspiration, Coupled With Rapid On-Site Evaluation (Without EBUS), In the Diagnosis of Thoracic Metastasis of Polypoid Melanoma: A Case Report. J Case Repo Imag 4: 029.

Copyright: © 2021 Lio E, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.