*Corresponding Author:

Maryna Neborachko,

Medical Advisor, MyDiabetesSolutions, Kyiv, Ukraine

Tell: +380663014030

Email: maryna.neborachko@gmail.com

Abstract

Insulin treatment is a necessity for the lives of patients with diabetes to maintain optimal blood glucose levels. In recent years, new Insulin Analogues (IA) and various insulin treatment regimens have been developed to meet these needs. On the other hand, new insulin formulations create higher costs, which may limit their use. Data comparing Recombinant Human Insulin’s (RHI) to IA, including meta-analyzes of comparative efficacy and safety, as well as cost-effectiveness data, summarized and discussed in this article. Despite active marketing of the newest formulations and their active promotion at the market, the professional medical approach should take into account all available data and require their comprehensive analysis.

Keywords

Biphasic insulins; Cost savings; Diabetes mellitus; Drug costs; Evidence-based practice; Health care costs; Insulins; Type 2

Introduction

Insulin treatment is a necessity for the lives of patients with diabetes to maintain optimal blood glucose levels. In recent years, new Insulin Analogues (IA) and various insulin treatment regimens have been developed to meet these needs. On the other hand, new insulin formulations create higher costs, which may limit their use. Factors such as the effectiveness of treatment, its safety and patient satisfaction should be taken into account when decision on choosing the right treatment made, but their cost also cannot be ignored, taking in consideration that these drugs are subject to reimbursement. In order to fulfill these prerequisites and to account for the chronic course of the disease, insulin therapy should be tailored individually to the patients’ needs, treatment goals, safety and costs. Global insulin market is growing and predicted to reach USD 76 bln till 2023 [1]. In view, that most of diabetes cases diagnosed in the countries with low and middle income, price should be seriously considered as one of the most important characteristics and marketing of the most expensive products should be responsible as never before. Currently, there is a wealth of data comparing Recombinant Human Insulin’s (RHI) to IA, including meta-analyzes of comparative efficacy and safety, as well as cost-effectiveness data as well, as data related to possible malignancy. Authors propose an analysis of these data regarding the appropriateness of usage IA vs RHI for type 1 (T1D) and type 2 (T2D) diabetes mellitus and their effectiveness in both types of diabetes.

Usage of RHI and IA for both T1D and T2D

According to Management of T2D The National Institute for the Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (2008) the recommendations were to usually start insulin treatment with human Neutral Protamine Hagedorn(NPH) insulin.However along-acting basal insulin may be considered in some circumstances such as special risk from hypoglycemia, and where twice daily injection is problematic [2]. In regards to joint Consensus of American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association of Study Diabetes (EASD) [3] the rapid-acting and long-acting IA have not been shown to lower A1C levels more effectively than the older, short-acting or intermediate- acting formulations [4-6]. According to ADA standards of medical care in diabetes-2018 most individuals with T1D should use rapid-acting IA to reduce hypoglycemia risk. In T2D it is recommended to initiate insulin therapy with basal NPH insulin and in case of lack of effectiveness to add one acting insulin before main meal or to switch to premixed insulins, in case of further lack of effectiveness to switch to pre-mixed IA or to add additional injection of acting insulin [7]. However, recent (2020) ADA standards of medical care in diabetes [8] already tells that doctors should consider basal insulins with low hypoglycemic effect to initiate insulin therapy in patients with T2D. Recommendations of European Society of Cardiologists (ESC), as well as EASD [9], have been edited the same way. Some National Guidelines recommend today an even more radical approach. In particular, Algorithms of Medical Care 2019 (Russia) provide direct recommendation to start insulin therapy in type 2 patients with IA. The United States, as a country that has already faced with a significant increase in diabetes-related costs, made a remark in ADA standards of care 2020 on the importance of insulin costs underlying that choice of basal insulin should be based on patient-specific considerations, including cost [10]. NICE T2D guidelines revised in 2019 [11] do not contain direct recommendation to start insulin therapy for T2D patients from IA, but recommends to start from a choice of a number of insulin types and regimens: offering NPH insulin injected once or twice daily in accordance with the need. It’s recommended to consider? starting both NPH and short-acting insulin (in particular, if the person’s HbA1c is 75 mmol/mol [9.0%] or higher), administered either: separately or as a pre-mixed (biphasic) RHI. AI as a alternative to NPH insulin is considered if the person needs assistance from a carer or healthcare professional to inject insulin, and use of insulin detemir or insulin glargine [12] would reduce the frequency of injections from twice to once daily or the person’s lifestyle is restricted by recurrent symptomatic hypoglycemic episodes or the person would otherwise need twice-daily NPH insulin injections in combination with oral glucose-lowering drugs. Consider pre-mixed (biphasic) preparations that include short-acting IA, rather than pre-mixed (biphasic) preparations that include short-acting RHI if a person prefers injecting insulin immediately before a meal or hypoglycemia is a problem or blood glucose levels rise markedly after meals. [11] We’ll write below about possible reasons why NICE hesitates to follow a common trend. There is also rather confusing data regarding usage of long acting IA in T1D and T2D they aren’t recommended for T1D, but recommended as a first choice for T2D in the latest ADA and ESC/ EASD standards.

Usage of premixed IA is a topic for another discussion

Premixed insulin formulations are among the most frequently used in many countries [13]. There are apparent differences in phar- macokinetic and pharmacodynamics properties between premixed insulin IA and conventional premixed RHI [14]. Whether the differ- ences possess a clinical importance remains a matter of discussion and surely depends on an individual patient clinical condition [12]. However, IA may not be suitable for all patients with diabetes. For many patients, a disadvantage regarding the application of IA may be a therapy expense [11, 12] as well as too short time of action among individuals by whom insulin formulation requires a longer time span for example, those who used to eat snacks. It is very important to im- plement insulin therapy to patients who are likely to adhere, because non adherency to pharmacotherapy has been linked to unfavorable outcomes [15].

Usage of RHI and IA for T2D

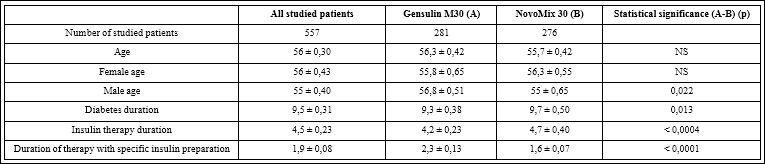

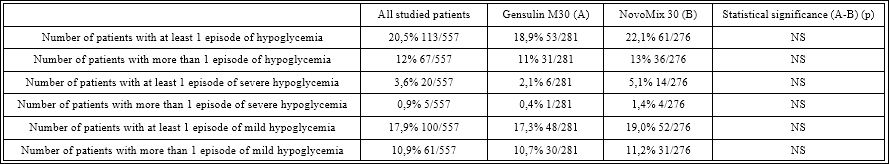

In Systematic Review “Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Premixed IA in T2D”16 studies that compared premixed IA with premixed RHI were analysed. The pooled analysis suggested that premixed IA provide similar HbA1c control to premixed RHI and similar fasting plasma glucose level control to premixed RHI. Premixed IA were more effective than premixed RHI in decreasing Postprandial Plasma Glucose (PPG) levels. Premixed IA may cause a similar rate of incidents of hypoglycemia as premixed RHI. Study’s conclusion is that premixed IA provide glycemic control similar to that of premixed RHI and may provide better glycemic control than long-acting IA and non insulin antidiabetic agents, but data on clinical outcomes are very limited [16]. The observational study PROGENS Benefit aimed to compare efficacy, safety, and quality of treatment satisfaction of premixed RHI and IA among T2D patients, showed that premixed insulin both IA and RHI are efficient and safe, and studied patients were satisfied with both treatment methods [17]. According to another study comparing of efficacy and safety of premixed RHI insulin (Gensulin M30) with premixed insulin Aspart 30/70 (NovoMix30) in patients with T2D [18] fasting plasma glucose FPG, PPG and HbA1c values did not differ significantly between subgroups of patients. Incidence of severe and mild hypoglycemia did not differ significantly between subgroups of patients. Treatment with pre-mixed insulin Gensulin M30 or NovoMix30 for at least half a year results in similar metabolic control of patients (FPG, PPG and HbA1c). Safety of treatment with pre-mixed RHI (Gensulin M30) or IA (NovoMix30) is similar. According to Review of the evidence comparing insulin (RHI or animal) with IA [13] in analyses that indicated statistically significant advantages for IA for glycaemic control, the differences between IA and RHI remain very small (ie 0.09%) and do not constitute clinically important differences. Consequently, the available evidence indicates that IA have no advantage over RHI for the outcome of glycaemic control. Regarding the occurrence of hypoglycemic events, IA appear to have statistically significant advantages compared to RHI, but these advantages are not consistent across types of insulin (rapid or long-acting) or types of diabetes, and the clinical importance of these differences is not clear. In addition, many trials which demonstrated a difference between IA and regular RHI for the occurrence of hypoglycemia excluded patients with a history of recurrent major hypoglycemia [19] therefore it may not be appropriate to assume such advantages will be observed across all patients. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of pre-mixed RHI (Gensulin M30) versus pre-mixed insulin aspart 30/70 (NovoMix 30) in patients with T2D were a main objectives of the POLGEN study [20]. Patients (557 persons) with T2D were divided into two groups – those, who received premixed RHI and IA Table 1. Any statistically significant differences in the level of main metabolic parameters related to diabetes mellitus (FPG, PPG, HbA1c) were noticed along the study between 2 groups Table 2. As well any statistically significant differences in frequency of hypoglycemic episodes were found between both groups Table 3.

Table 1: Number of patients, age, duration of diabetes, and duration of treatment with specific insulin preparation (X ± SEM).

|

|

All studied patients |

Gensulin M30 (A) |

NovoMix 30 (B) |

Statistical significance (A-B) (p) |

|

Mean of lowest fasting blood glucose concentrations (mg/dl) |

109 ± 1,36 |

110 ± 1,64 |

108 ± 1,57 |

NS |

|

Mean of highest fasting blood glucose concentrations (mg/dl) |

150 ± 1,49 |

151 ± 2,03 |

149 ± 2,18 |

NS |

|

Mean of lowest postprandial blood glucose concentrations (mg/dl) |

131 ± 1,53 |

132 ± 2,27 |

130 ± 2,04 |

NS |

|

Mean of highest postprandial blood glucose concentrations (mg/dl) |

187 ± 2,00 |

189 ± 2,94 |

185 ± 2,72 |

NS |

|

HbA1c (%) |

7,52 ± 0,05 |

7,55 ± 0,07 |

7,54 ± 0,08 |

NS |

|

HbA1c - female (%) |

7,52 ± 0,07 |

7,55 ± 0,08 |

7,48 ± 0,10 |

NS |

|

HbA1c - male (%) |

7,58 ± 0,08 |

7,54 ± 0,10 |

7,60 ± 0,11 |

NS |

|

HbA1c ≤ 6,5 (%) |

12,9 |

10,3 |

15,6 |

NS |

|

HbA1c > 6,5(%) |

87,1 |

89,7 |

84,4 |

NS |

|

HbA1c ≤ 7,0 (%) |

34,1 |

32,4 |

34,1 |

NS |

|

HbA1c > 7,0(%) |

65,9 |

67,6 |

65,9 |

NS |

Table 2: Fasting and postprandial blood glucose, HbA1c valued in the study population and specific groups.

Table 3: Incidences of severe and mild hypocalcemia in the study subjects.

Another systematic review and meta-analysis included eight studies comparing the effects of long-acting IA to RHI in patients with T2D. Six studies investigated insulin glargine and two insulin detemir. No superiority in HbA1c was observed for insulin glargine. For insulin detemir the meta-analysis yielded a statistically significant but clinically unimportant superiority of RHI in metabolic control. Symptomatic and nocturnal hypoglycemic events were lower in patients treated with insulin glargine than in patients with RHI therapy. Also, for insulin detemir the two studies found a lower number of patients experiencing overall or nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes in the insulin detemir treatment groups. The methodological quality of the included studies allowed only a cautious interpretation of the results. Up till now, no study designed to investigate possible longterm effects was found. Therefore, it remains unclear if and to what extent the treatment with long-acting IA will affect the development and progression of microvascular and macrovascular events compared to results obtained with RHI. Since the differences in overall effects on metabolic control were only small for insulin glargine and RHI and even disadvantageous for insulin detemir, no important improvements in the development of microvascular late complications would be expected from treatment with long-acting IA. As for the advantages found in the rate of severe hypoglycemic events some caution is warranted. No statistically significant advantage was found for therapy with insulin glargine or detemir. Also, interpretation of the results of the frequency of severe hypoglycemia is difficult due to bias-prone definitions. Patients may inappropriately deny severe hypoglycemia and in this context “third party help” is a soft and variable description of severity. More robust definitions as “injection of glucose or glucagon by another person”may result in more reliable data [21]. In all studies the frequency of severe hypoglycemia was very low, making it unlikely to see an important clinical effect for the different treatments. Even though the meta-analysis found a consistent reduction in symptomatic or overall hypoglycemic effects for therapy with long-acting IA, no safe inferences can be drawn from these results because defining hypoglycemia by symptoms only makes the results prone to bias, especially in open trials with (likely) no blinded outcome assessment. The advantage of insulin glargine and detemir could be a lowering of nocturnal hypoglycemic events in patients with T2D mellitus and treatment with basal insulin. But again, bias cannot be ruled out and thus makes the interpretation of the results difficult. No trial reported data on quality of life. One trial reported data on treatment satisfaction [22] and reported a more pronounced improvement in therapy satisfaction in patients treated with insulin glargine. The interpretation of the clinical importance of this result is hindered by the fact that baseline and end of trial values are reported even though the trialists claim a statistically significant improvement in the change of treatment satisfaction. Additionally, the reporting of this outcome was poor and therefore the assessment of the quality of this outcome was not possible. Short-acting IA versus RHI in patients with DM were investigated in Cochrane Review. The main objective of this systematic review was to assess the effects of short-acting IA in comparison to RHI in patients with T1D and T2D. Were found no statistically significant differences in long-term metabolic control (HbA1c) between short-acting IA compared to RHI in patients with T2D; no statistically significant differences in overall hypoglycemic episodes between short-acting IA compared to RHI in T2DM patients: 3 studies (one double blind, two open design) found no significant difference between RHI and IA; 4 studies observed improvement in patients’ treatment satisfaction in the IA group (mainly due to the changes in convenience, flexibility and continuation of treatment as well as injection-meal interval). As a conclusion the systematic review suggests only a minor clinical benefit of short-acting IA in the majority of patients treated with insulin [4]. Another study compared fast-acting IA vs RHI (long-acting IA vs NPH and ready-made mixtures of IA vs ready-made mixtures of RHI) in patients with T1d and T2D and women with gestational diabetes. The aim of the study was to determine the benefits in terms of glycemic control and possibility to reduce the risk of complications and side effects. A systematic review of randomized clinical trials was conducted. The results showed that the differences in HbA1c levels and the incidence of hypoglycemia were insignificant and can’t be considered as clinically significant. In accordance with the opinion of the authors of the study, IA do not have advantages in terms of glycemic control, but can be useful in the treatment of patients with repeated hypoglycemia while optimizing the existing treatment with RHI. The routine use of long-acting IA in T2D is not recommended due to the high cost/effectiveness ratio [23]. Rapid acting IA have significantly different pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics compared to RHI. Based on these results, it is widely believed that regular RHI should be administered 20-30 minutes before a meal in order to lower the concentration of glucose in postprandial blood compared to IA administered immediately before a meal. The interval between injection and food intake for patients with T2D is not necessary [24]. A systematic review of 28 studies (10 with type 2 diabetes) showed that short-acting RHI and the rapid acting IA (aspart) helped to achieve identical glycemic control in T2D, and that the same results were achieved when evaluating HbA1c and the incidence of hypoglycemia, including risk of severe hypoglycemia. In this case, short-acting RHI showed the best results for the control of FPG, and the rapid acting IA (aspart) showed the best results for the control of PPG [25]. Another study conducted in Germany showed that the long-term benefits of using long-acting IA for T1D as a whole have not been adequately studied, and there is no evidence of the benefits of insulin glargine and insulin detemir compared with NPH insulin [26]. The study of the use of long-acting IA in T2D [27] showed that patients who are not on intensive insulin therapy have no evidence of the benefits of insulin glargine and insulin detemir compared with NPH insulin; during intensive insulin therapy, the basal insulin regimen in combination with oral hypoglycemic drugs also lacks evidence of the benefits of insulin glargine and detemir insulin compared to insulin NPH, provided that RHI therapy has been optimized. It was noted that, in general, the long-term benefit of using long-acting IA in terms of the impact on the development of late complications of diabetes is not well understood. A study of the use of fast-acting IA in T1D [28] showed that the benefits of aspart as compared to RHI in adult patients are not obvious because of lack of data; in patients with a higher than average risk of hypoglycemia, the same result was demonstrated with the use of lyspro insulin and RHI, and the benefits of lyspro insulin in patients with a high risk of severe hypoglycemia are not obvious; due to the lack of data, we can’t talk about the advantage of insulin glulisine compared with RHI. Another analysis suggests, if at all only a minor clinical benefit of treatment with long-acting IA for patients with T2D treated with “basal” insulin regarding symptomatic nocturnal hypoglycemic events. Until long-term efficacy and safety data are available, we suggest a cautious approach to therapy with insulin glargine or detemir [4].

Cost-effectiveness approaches to insulin treatment

Cost-effectiveness estimates of IA vary widely, from just over €500 to greater than £412,000 per Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) gained. Estimates indicating cost-effectiveness are generally specific to a particular population and regimen, however the broader and more comprehensive analyses indicate that IA appears to lack cost-effectiveness. There remains a lack of evidence addressing longer-term outcomes of diabetes such as mortality and long-term complications. Given the lack of clear benefits for IA for glycaemic control as well as the inconsistent and clinically debatable benefits for occurrence of hypoglycemia, along with concerns about trial quality, the current evidence does not indicate a strong advantage for IA compared to RHI for both T1D and T2D. World Health Organization has refused to add IA to the list of essential medications for 2 times. Thus, in 2011 it was stated that for T1d and T2D rapid and long-acting IA do not show pronounced advantages compared to RHI against the background of scattered statistical data on the positive properties and the absence of clinically significant advantages. It has not been proven that IA is cost-effective, and the relationship between IA and an increased risk of cancer is still uncertain. An expert committee noted a lack of data on the benefits of IA over RHI. The committee evaluated the available data regarding the effect of IA on the HbA1c reduction rate and the incidence of hypoglycemia as modest and not justifying the current significant price difference between IA and RHI. Based on this assessment, the Expert Committee did not recommend the addition of long-acting IA as a pharmacological class to the main list of essential medicines for the treatment of T1D in adults, adolescents, and children aged 2 years and older [8]. Almost the same conclusion was made in 2017 [1] An expert committee noted a lack of data on the benefits of IA over RHI. The committee evaluated the available data regarding the effect of IA on the HbA1c reduction rate and the incidence of hypoglycemia as modest and not justifying the current significant price difference between IA and RHI. Based on this assessment, the Expert Committee did not recommend the addition of long-acting IA as a pharmacological class to the main list of essential medicines for the treatment of T1D in adults, adolescents, and children aged 2 years and older.The cost-effectiveness of IA depends on the type of IA and whether the patient receiving the treatment has T1D or T2D. With the exception of rapid-acting IA in T1D, routine use of IA, especially long-acting ones in T2D, is unlikely to represent an efficient use of finite health care resources [13]. According to the National Health Service (NHS) report of prescribing IA over the 10-year period (from 2000 to 2009), [29] the NHS spent a total of £2732 million on insulin (cost was adjusted for inflation and reported in UK pounds at 2010 prices). The total annual cost increased from £156 million to £359 million, an increase of 130%. The annual cost of IA increased from £18.2 million (12% of total insulin cost) to £305 million (85% of total insulin cost), whereas the cost of RHI decreased from £131 million (84% of total insulin cost) to £51 million (14% of total insulin cost). If it is assumed that all patients using IA could have received RHI instead, the overall incremental cost of IA was £625 million.

This investigation concluded that given the high marginal cost of IA, adherence to prescribing guidelines recommending the preferential use of RHI would have resulted in considerable financial savings over the period. The case of Great Britain is widely known, in which the cost of insulin therapy for patients with T2D increased 3 times during the period 1997-2007, mainly due to the use of expensive IA. However, an improvement in HbA1c level was achieved only at the level of -0.1% (8.5-8.4%). In the event that within 5 years, 50% of people received RHI instead of IA, it would be possible to additionally employ 400 doctors or 1,000 specialized diabetic nurses.The experience of insulin therapy in the UK shows that the clinical benefits of IA do not correlate with their high price, there are no obvious clinical advantages of using IA in most patients. Given the high cost of IA, compliance with guidelines recommending the predominant use of RHI would lead to significant financial savings over this period [30]. Apparently, thanks to such an objective analysis, the current British recommendations do not contain such direct recommendations for the appointment of IA for T2D, as recommendations from other countries. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, Germany’s leading quality control organization, also concluded that IA (rapid and long-acting) have no advantages over RHI, and therefore the cost difference between IA and RHI is assessed as unacceptable. In 2006, G-BA, the Joint Federal Committee (Decision Center in German Health Care), decided not to finance the use of rapid acting Ia for T2D. This has led to a reduction in the cost of these drugs to the level of human insulin. In 2009 and 2010, G-BA decided not to compensate for the cost of long-term IA for people with T2D and T1D and rapid term IA for people with T1D until their price is reduced to the price of RHI. It was decided that reimbursement should be continued only in case of allergy to RHI and at high risk of severe hypoglycemia [31].

The results of a meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of IA for the management of diabetes mellitus indicate that IA offer few clinical advantages over conventional insulins in the management of most patients with T1D, T2D or gestational diabetes. Although the evidence supporting the benefit of IA in terms of hypoglycemia is weak, [32] these agents may be an option for patients with problematic hypoglycemia despite optimization of conventional insulin therapy. In a companion paper (see page 369 of this issue), we report on the cost-effectiveness of IA in the management of T1D and T2D in adults. The results of the cost-effectiveness analysis serve to clarify further the optimal place of IA relative to conventional insulins in the management of diabetes in the Canadian health care system [33].

Discussion

Using the above data the authors urge the necessity for all insulin market players to think about optimizing the costs to cover the needs of people with diabetes. Unmotivated increase of the costs due to raising the cost of insulin therapy may cause long-term consequences for this vulnerable category of patients. The current situation insistently emphasize the need of effective program policies to be implemented: first, to optimize the costs and, second, to increase the ubiquitous availability of insulin. These two interrelated processes along with the popularization of non-drug approaches and necessary lifestyle changes (diet modification, physical activity, smoking cessation, etc.) should become cornerstones of helping people with diabetes. Another mandatory approach should be the analysis of the long-term use of different types of insulin, first of all, IA in comparison with RHI in terms of the development of late complications of diabetes. The last radical paradigm shift in insulin therapy-the abandonment of the use of animal insulin-has led to, at least, an almost complete disappearance of the complications of insulin therapy. What changes do we expect to get in regards to the massive abandonment of human insulin in favor of insulin analogues? By what parameters does the scientific community plan to evaluate the effectiveness of this step? If we do not have a clear answer, we should think twice before prescribing modern but expensive drugs.

Conclusion

Reasonable policies of use of insulin therapy should be developed based on available clinical evidence data based on comparative studies in different groups of patients with diabetes mellitus and comprehensive economical data analysis. Advisability of use of a new product should be estimated and regularly revised based on the practical results of its implementation in clinical practice. Retrospective cost-effective analysis for evaluation of pharmacoeconomical benefits should be also implemented on a regular basis. All these steps should help decision makers and regulators to implement effective National programs with developing new efficient systems of insulin purchases.

References

- Moja L (2017) Report of the 21st WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines WHO headquarters. Ge- neva 27-31.

- Sibal L (2009) Management of type 2 diabetes: NICE guidelines. Clinical Medicine 9: 353-357.

- Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Ferrannini E, Holman RR, et al. (2009) Medical Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Dia- betes: A Consensus Algorithm for the Initiation and Adjustment of Therapy. A consensus statement of the American Diabetes Associ- ation and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 32: 193-203.

- Horvath K, Jeitler K, Berghold A, Ebrahim SH, Gratzer TW, et al. (2007) Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes The Cochrane Library 3.

- Raskin P, Allen E, Hollander P, Lewin A, Gabbay RA, et al. (2005) Initiating insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28: 260-

- Dailey G, Rosenstock J, Moses RG, Ways K (2004) Insulin glulisine provides improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 Diabetes Care 27: 2363-2368.

- American Diabetes Association Standards of Diabetes Care in Dia- betes -2018. Diabetes care 41: S1-S2.

- American Diabetes Association, Standards of Diabetes Care in Dia- betes – Diabetes care, Volume 43: S1-S2.

- Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, et al. (2020) 2019 ESC Guidelines on Diabetes, Pre-Diabetes and Car- diovascular Diseases Developed in Collaboration with the EASD. European Heart Journal 41: 255-323.

- Rajkumar SV, The High Cost of Insulin in the United States An Urgent Call to Mayo Clin Proc 95: 22-28.

- NICE guideline Published: 2 December 2015 Last updated August

- Holden SE, Poole CD, Morgan CLl, Currie CJ (2011) Evaluation of the incremental cost to the National Health Service of prescribing analogue BMJ Open.

- 18th Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines (Accra, Ghana, 21 to 25 March 2011). Review of the evidence comparing insulin (human or animal) with analogue insulins.

- Cameron CG, Bennett HA (2009) Cost-effectiveness of insulin ana- logues for diabetes mellitus . CMAJ 180: 400-407.

- Siebenhofer A, Plank J, Berghold A, Jeitler K, Horvath K, et al. (2006) Short acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin in patients with diabetes CochraneDatabase of Systematic Reviews 2.

- Qayyum R, Bolen S, Maruthur N, Feldman L, Wilson LM, et al. (2008) Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Premixed Insulin Analogues in Type 2 Ann Intern Med 149: 549-559.

- Nabrdalik K, Kwiendacz H, Sawczyn T, Tomasik A, Kukla M, et al. (2018) Efficacy, Safety and Quality of Treatment Satisfaction of Pre- mixed Human and Analogue Insulin Regimens in a Large Cohort of Type 2 Diabetic Patients PROGENS BENEFIT Observational International Journal of Endocrinology.

- Wladyslaw Grzheschak at al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of premixed human insulin (Gensulin 30) vs premixed insulin Aspart 30/70 (NovoMix 30) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Inte- grated diabetes

- Singh SR, Ahmad F, Lal A, Yu C, Bai Z, et al. (2009) Efficacy and safety of insulin analogues for the management of diabetes melli- tus: A meta-analysis. CMAJ 180: 385-397.

- Grzeszczak W (2010) i wsp, POLGEN study. Diabetologia Doświ- adczalna i 10: 53-59.

- Mühlhauser I, Overmann H, Bender R, Bott U, Berger M (1998) Risk factors of severe hypoglycemia in adult patients with type 1 diabetes-a prospective population based study. Diabetologia 41: 1274-1282.

- Eliaschewitz FG, Barreto T (2016) Concepts and clinical use of ul- tra-long basal Diabetol Metab Syndr 8: 2.

- Singh SR, Ahmad F, Lal A, Yu C, Bai Z, et al. (2009) Efficacy and safety of insulin analogues for the management of diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 180: 385-397.

- Müller N, Frank T, Kloos C, Lehmann T, Wolf G, et al. (2013) Diabetes Care Diabetes Care 36: 1865-1869.

- Rys P, Pankiewicz O, Łach K, Kwaskowski A, Skrzekowska-Baran I, et (2011) Efficacy and safety comparison of rapid-acting insulin aspart and regular human insulin in the treatment of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab 37: 190-200.

- Long-acting insulin analogues in the treatment of diabetes mellitus type 1. Executive summary of final report A05-01, Version 1.0.

- Langwirksame Insulinanaloga zur Behandlung des Diabetes mellitus Typ 2. (2009) Version 1.1

- Insulin analogues for diabetes mellitus: review of clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health HTA Issue 33, October

- Gale EA (2000) A randomized controlled trial comparing insulin lispro with human soluble insulin in patients with Type 1 diabetes on intensified insulin therapy The UK Trial Diabetic Medicine 17: 209-214.

- 18th Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines (Accra, Ghana, 21 to 25 March 2011) REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE COMPARING INSULIN (HUMAN OR ANIMAL) WITH ANALOGUE INSULINS.

- Krzystof Strojek (2008) Gensulin M30 in patients with type II diabetes mellitus and secondary failure of oral antidiabetic drugs. The Progens-first-step study: a multicenter observational study in the outpatients setting. Diabetologia Doswiadczalna i Kliniczna 8: 91-94.

- Zammitt NN, Frier BM (2005) Hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:2948-2961.

- Miller CD, Phillips LS, Ziemer DC, Gallina DL, Cook CB, et al. (2001) Hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Int Med 161: 1653-1659.

Citation: Neborachko M, Pkhakadze A (2020) Do All Evidences Say That The Insulin Analogues Are More Effective Than Human Insulins. J Diab Meta Syndro 3: 009.

Copyright: © 2020 Neborachko M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.