*Corresponding Author:

Joel Weiner,

Division of Neonatology, De- partment of Pediatrics, University of Massachusetts Memorial Hos- pital, 119 Belmont Street, Worcester, MA, 01605, USA

Tel: 508-334-6206

Fax: 508-603-1226

Email: jtteupton@aol.com

Abstract

Background

A key component of “choosing wisely in neonates” is the discontinuation of unnecessary antibiotic therapy [1]. Early and prolonged exposure to antibiotics in the Newborn Intensive Care Unit (NICU) has been associated with significant mortality and morbidities, particularly an increase in Late-Onset Sepsis (LOS). We implemented an early-onset rule-out protocol that allowed for discontinuation of antibiotics after 24 hours.

Methods

Beginning in April 2012, if two blood counts, 12 hours apart were normal and blood cultures were negative at age 24 hours, antibiotics were discontinued. For the next three years, all infants started on antibiotics on the day of birth were monitored for rates of Early-Onset Sepsis (EOS), LOS and Necrotizing Entero-Colitis (NEC).

Results

Of 1243 newborns, 741 (59.6%) had their antibiotics discontinued after 24 hours, resulting in 2223 fewer doses of antibiotics. LOS was 6.1%, significantly lower than NICHD Neonatal Network (NRN) LOS (24.6%), Vermont Oxford Network (VON) (13.6%) (2009-2015) and a literature survey rate (18%) (all P < 0.001).

Conclusions

When it is necessary to rule out sepsis at birth, it is feasible and safe to discontinue antibiotics within 24 hours in select infants. These results comply with JCAH antibiotic stewardship because of reduced antibiotic therapy, less LOS and reduced costs.

Keywords

Quality improvement; Sepsis; Antibiotics; Newborn; Early-onset

Abbreviations

BW: Birth weight

ELBW: Extremely low birth weight EOS: Early-onset sepsis

LOS: Late-onset sepsis

NEC: Necrotizing enterocolitis

NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

NPV: Negative predictive value

NRN: NICHD Neonatal Network

VLBW: Very low birth weight

VON: Vermont Oxford Network

WBC: White blood count

Introduction

Overuse of antibiotics has been described in veterinary, adult and pediatric medicine. NICU’s are not exempt from this problem. There have been both long and short-term associations found with antibiotic exposure in infancy, likely influenced by the alteration in the neonatal microbiome [2]. Long-term associations include an increase in child- hood obesity [3], early wheezing [4], asthma [5], inflammatory bowel disease [6], renal injury and ototoxicity [7]. Short-term associations include an increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis [8], bronchopul- monary dysplasia [9], death [10] and LOS, both in preterm [11] and term [12] infants.

Attempts to decrease antibiotic exposure in neonates are com- plicated by guidelines that recommend treating selected infants de- spite negative blood cultures if labs are abnormal [13]. Furthermore the conundrum of “culture-negative” or “presumed” sepsis continues to complicate the issue of which babies should be treated with a full course of antibiotics, which is arbitrarily defined, even though blood cultures remain negative. Hundreds of studies have attempted to clarify the utility of various laboratory tests to predict which newborns are infected. All of these tests have shown poor specificity and positive predictive value. The goal of our study was to assess the potential of laboratory tests to predict the non-infected infant.

In 2012 we reported on a retrospective review of two decades of data examining the Negative Predictive Value (NPV) and sensitivi- ty of two White Blood Counts (WBC) and differentials obtained ~12 hours apart along with a blood culture result at 24 hours of age in predicting sepsis outcome among newborns evaluated for sepsis and begun on antibiotics [14]. All infants with either culture-proven infec- tion or “presumed, clinical sepsis” had either a positive blood culture or abnormal blood count. The NPV and sensitivity were 100%. During those two decades approximately 50% of babies had two normal WBC and differentials (WBC between 6000 and 30,000 and a band:neutro- phil ratio < 20%) [14] along with a negative blood culture at 24 hours of age, suggesting that discontinuation of antibiotics after 24 hours of coverage may be a feasible alternative in selected infants.

We prospectively examined the impact of discontinuing antibiot- ics at 24 hours using these criteria. We further wished to determine if early (after 24 hour coverage) discontinuation of antibiotics in infants ruled out for sepsis at birth was feasible for infants admitted to our NICU. We also assessed the impact on LOS in a NICU setting that minimizes or avoids multiple factors that have been associated with an increased risk of LOS (including early steroids, prolonged antibiotics, antacids, etc) as compared to published literature.

Methods

The NICU at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center is the only level 3 NICU serving central Massachusetts. We have be- tween 600 to 700 admissions per year, of whom 100 to 120 are VLBW. Approximately 35 to 40 infants admitted yearly are < 28 weeks gesta- tional age. All services are provided in our NICU with the exception of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) and complex congenital heart surgery. We are a teaching institution with Neonatal fellows and residents. The average daily census is between 45 and 55 infants.

Prior to April, 2012, infants admitted to our NICU were begun on antibiotics (Ampicillin q 12 hours and Gentamicin q 24-48 hours depending on gestational age) if they met specific criteria, including: (i) Less than 35 weeks gestational age (unless delivered for maternal indications without labor or rupture of membranes, for example, a ce- sarean section for worsening preeclampsia). (ii) Two or more major risk factors including prolonged rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours, premature labor and/or maternal fever (if thought to be associated with chorioamnionitis). (iii) Symptoms including respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, hypotension and/or clinical instability. Antibiotics are discontinued at 48 to 72 hours if: (i) WBC at birth and at ~12 hours of age are normal (total and differential) and blood culture is negative. (ii) Initial WBC (one or both) are abnormal but normalize on subse- quent screens and (iii) WBC are persistently abnormal (leukocytosis and/or abnormal differential) but CRP is normal at ~72 hours of age (< 10 mg/L). If the initial WBC exhibited leukopenia (in absence of maternal preeclampsia/hypertension) and an abnormal differential, the antibiotics were usually continued for a 7 day course for presumed sepsis. Infants were not continued on antibiotics past 48 to 72 hours for symptoms alone if the above criteria were met for discontinuation of antibiotics.

In April of 2012, we commenced a pilot quality improvement proj- ect prospectively evaluating all infants admitted and ruled-out for sep- sis. A blood culture and two complete blood counts were drawn with- in 12 hours. We revised our early-onset protocol to include the option to discontinue antibiotics after 24 hours of coverage if the culture was negative and blood counts normal. We prospectively followed all ba- bies admitted to our NICU to assess whether this approach continued to prove to be applicable and safe, as well as monitor for outcomes during the NICU stay. Particular attention was paid to LOS as, in ad- dition to the above protocol, overall antibiotic use in our unit is de- creased to that described in the neonatal literature. If associated with less alteration in the newborn microbiome, this may contribute to a decrease risk of late infections.

All infants were followed prospectively through March, 2015. For safety purposes outcomes were analyzed every 6 months. Data col- lected included number of infants with antibiotics discontinued after 24 hours of coverage, and those who required a longer duration of antibiotics. We recorded the number of infants with EOS, “presumed” or “culture-negative” sepsis, LOS, mortality and incidence of NEC. We compared our infection outcomes to those of the NICHD NNR pub- lished in 2015 [15], VON rates from 2009-2015 [16] and to LOS rates obtained from a survey of recent neonatal literature (Appendix).

Data Analysis: For our cohort, as well as the NICHD data, we calculated proportions and their associated 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI). These proportions were further stratified over gestational age and birth weight. P values were obtained by simple Z tests for dif- ferences between proportions.

The study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medi- cal School Institutional Review Board.

Results

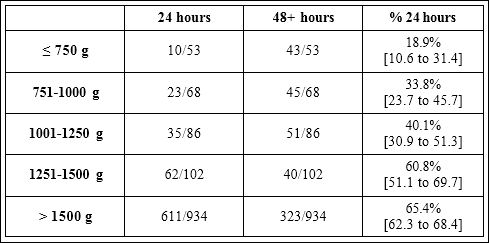

Over the 3 year study period, a total of 1243 newborns were ad- mitted to our NICU and evaluated/treated to rule-out EOS (Table 1). This represents 63% of all admissions to our NICU. Antibiotics were discontinued after 3 doses (24 hours of coverage) in 741 (59.6%) and continued for a minimum of 48-72 hours of coverage in 502 (40.4%). The latter group received on average 5.9 doses of antibiotics. Antibi- otics were not discontinued after 24 hours because of 1 or 2 abnormal WBC/differential counts.

Table 1: Number of Worcester Memorial Hospital babies whose antibiotics were discontinued at 24 and 48 hours, according to their birth weight. Labels represent the percentage of babies whose antibiotics were discontinued at 24 hours, with its associated 95% confidence interval.

There were 11 cases of documented early-onset sepsis (0.7%) (E coli (3), Group B Strep (3), Strep Viridans (2), other (3)) and 23 cas- es (1.8%) of “culture-negative” or “presumed” sepsis. The latter group received one week of antibiotics due to persistently abnormal WBC/ differential counts along with an abnormal CRP (> 10 mg/L) at ~72 hours of age. The majority of the remaining 468 newborns had their antibiotics discontinued at 48-72 hours with a few infants receiving 72-96 hours of therapy.

The likelihood of antibiotics being discontinued after 3 doses in- creased with increasing birth weight (Table 1). Infants > 1500 grams BW had a 3.7 times greater likelihood of early discontinuation of antibiotics compared to infants ≤ 750 grams. Approximately 27% of ELBW infants (< 1000 grams BW) and 52% of VLBW (1000-1500 grams BW) met criteria for antibiotic discontinuation after 3 doses.

There was no significant difference between the 24 hour coverage group and the 48+ hour group in the incidence of LOS or NEC (≥ 2A). There were also no significant differences between groups in number of ELBW or VLBW infants on > 5 total days of antibiotics during the hospital stay (Table 2).

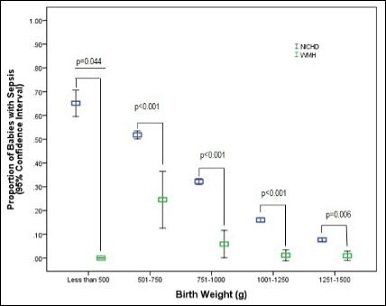

The early discontinuation group received 2223 fewer doses of an- tibiotics over the 3 year study period. The incidence of LOS in the literature review (primarily 2010 through 2016) of 52 studies compro- mising 501,578 infants (mean 18%; range 11.5-82%, median 27.6%) (Appendix), the 2013 NICHD study (mean 24.4%) (Figures 1 & 2) and the VON rate (mean 13.6%) were all significantly greater than the in- cidence in our NICU (mean 6.1%). This was true across all gestational ages and birth weights.

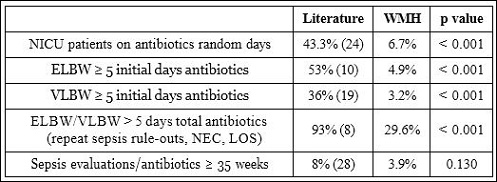

Multiple measurements of antibiotic stewardship also measured significantly different in our NICU as compared to the literature (Table 3). This included random day assays of the number of patients on antibiotics, ≥5 initial days on antibiotics for both ELBW & VLBW infants and total days on antibiotics during the hospitalization for in- fants < 1500 grams.

Discussion

Our current prospective quality improvement protocol suggests that discontinuation of antibiotics after 24 hours of coverage in newborns having sepsis ruled out in the first 24 hours of age is possible in the majority of these infants. In the 3 year period of our study, this resulted in a savings of over 2200 doses of antibiotics. This has potential benefits of decreasing IV needs, reducing medication errors, lessening painful procedures and decreasing the impact of antibiotics on the intestinal microbiome [2].

Table 2: Incidence of Late-Onset Sepsis (LOS) and Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) at Worcester Memorial Hospital according to duration of antibiotic therapy, and > 5 days total antibiotic exposure.

Exposure to antibiotics in the newborn period has been associated with profound effects on intestinal bacteria. Turcu [17] demonstrated the early exposure to antibiotics was associated with a decrease in stool diversity scores. A recent study in ELBW evaluated 6 week biodiversity scores and found they were inversely correlated to duration of antibiotic exposure [18]. Johnson [19] found that complete recovery of initial bacterial composition was rarely achieved after initial alteration due to antibiotic treatment.

Figure 1: Proportion of babies with Late Onset Sepsis (LOS) according to gestational age, comparing the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) data to those obtained at the Worcester Memorial Hospital (WMH) between April 2012 and March 2015.

Figure 2: Proportion of babies with Late Onset Sepsis (LOS) according to birth weight, comparing the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) data to those obtained at the Worcester Memorial Hospital (WMH) between April 2012 and March 2015.

Table 3: Various indices of antibiotic stewardship at Worcester Memorial Hospital and overall number of sepsis evaluations preformed in infants > 35 weeks gestational age.

Multiple recent studies supported an association between prolonged initial antibiotic exposure in neonates and late-onset sepsis. [10,12,20]. This broad exposure to antibiotics occurs both in the immediate newborn period as well as during hospitalization in the NICU. In a survey of over 5500 ELBW infants, Cotton found that 53% received ≥ 5 days of initial antibiotics despite negative cultures [10]. Kuppala found similar results in 36% of VLBW infants [19]. Approximately 93% of a cohort of 124 babies with NEC and 248 controls received over 5 days of antibiotics during their hospital stay [8]. Finally a survey of 29 NICU’s on two random days found that 43.3% of infants were on antibiotics with 18.8% on 3 or more drugs at the time of the survey [21]. All of these studies found that the majority of drug use was empiric rather than therapeutic.

Multiple factors have been associated with an increase in the risk of LOS in neonates, including: (i) the use of broad spectrum antibiotics [22], (ii) early corticosteroid exposure [23], (iii) use of H2 receptor antagonists [24], and (iv) the presence of indwelling intravascular catheters [25]. Our unit minimizes the empiric use of Cephalosporins and Vancomycin, does not use corticosteroids before 4 weeks of age for blood pressure support or for lung disease, rarely uses H2 receptor antagonists and removes umbilical catheters usually in less than 5 days, likely contributing to the low rate of LOS we report.

Our incidence of LOS in the highest risk infants (500-1500 grams, 23-32 weeks) is 2.1 to 13.3 times less than comparable newborns in the NRN [15] and approximately 4.9 times less than in the literature survey (Appendix) which included NICU’s in countries with well-developed medical systems (U.S., Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, etc) and a minimum of 100 subjects enrolled. Both multicenter and single center studies were included.

What complicates the initial attempt to determine which babies to evaluate for sepsis, whom to treat and how long to treat is a lack of evidence-based guidelines. Recommendations are available from both the Red Book [26] and the Committee on Fetus and Newborn (COFN) [13] but there are some areas of conflicts and lack of clarity on the approach to the “culture-negative” conundrum. The Red Book offers no recommendations on the approach to these infants while COFN has issued varying guidelines, initially recommending treating all babies with a prolonged course of antibiotics if the mother had chorioamnionitis, the infant was well, had negative blood cultures but an abnormal screening lab such as a WBC or CRP [27]. This was modified to not treating term infants with the above scenario but no change in the recommendation for preterm infants [28]. As our data show, 58% of infants < 1500 grams will have an abnormal WBC thus resulting in a large number of newborns receiving prolonged antibiotics despite negative cultures if these recommendations are followed.

Rather than relying on laboratory tests with poor positive predictive value and specificity, we chose to try and assess the sensitivity and negative predictive value of serial WBC and a baseline culture to try and predict non-infected babies allowing for earlier discontinuation of antibiotics in a select population. Of the 1243 babies ruled out for sepsis in our NICU, 97.7% were free of sepsis and received either a 24 hour coverage period or ~48-72 hour coverage. We have now had over a quarter of a century of 100% sensitivity/NPV in our unit using the previously described guidelines for serial WBC’s and blood cultures [14]. The ability to discontinue antibiotics in almost 60% of our infants after 3 doses combined with a minimizing of the diagnosis of “culture-negative” sepsis has allowed for decreased overall antibiotic exposure in our NICU. If extrapolated to the U.S., if approximately 500,000 newborns receive antibiotics at birth, close to 1 million doses of antibiotics would not need to be administered if these guidelines were applicable. Indeed a report from the Pediatrix group indicated a cost savings in excess of $20 million by reducing antibiotic administration to three days for “rule-out” sepsis. Extrapolating on a national basis the savings would be substantial [29].

No differences were found in the incidence of LOS between our two groups. This is likely due to both groups being exposed to what are considered short courses of antibiotics (3 vs. 5.9 doses). In order to find if this minimal decrease in dosing has a clinical effect, it is likely that many thousands of infants would need to be studied.

The limitations in this study include the uncertainty of extrapolating data from a single NICU to other units. Also, many NICU’s continue antibiotics for > 48-72 hours based on symptoms and/or risk factors. It would require a change in practice management to adopt a 24 hour rule out when many infants with negative laboratory evaluations are continued on antibiotics.

Conclusion

- Newborns with 2 normal WBC and a negative blood culture in our NICU have been shown over > 25 years to be free from infection (14). Discontinuation of antibiotics after 24 hours of coverage appears to be feasible with many likely advantages (decreased potential for drug errors, decrease in IV placements, decrease costs, potential for earlier discharge, less time separated from parents).

- No difference was demonstrated between the early discontinuation and the standard sepsis rule-out groups, though fewer ELBW and VLBW infants were exposed to > 5 total days of antibiotics in the early

- Earlier studies finding an association between prolonged antibiotic exposure (doses and days) and LOS would appear to be supported by our data.

- Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS), is a set of coordinated strategies to improve the use of antimicrobial medications with the goal to enhance patient health outcomes, reduce antibiotic resistance and decrease unnecessary costs. It is mandated by the JCAH. This study fulfills the criteria for antibiotic stewardship resulting in less antibiotic administration, reduced costs and reduced rates of LOS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Avroy A Fanaroff, MD for his re- view of the manuscript and multiple suggestions. His assistance was invaluable.

References

- Ho T, Dukhovny D, Zupancic JA, Goldmann DA, Horbar JD, et al. (2015) Choosing Wisely in Newborn Medicine: Five Opportunities to Increase Pediatrics 136: 482-489.

- Greenwood C, Morrow AL, Lagomarcino AJ, Altaye M, Taft DH, et al. (2014) Early empiric antibiotic use in preterm infants is associated with lower bacte- rial diversity and higher relative abundance of Enterobacter. J Pediatr 165: 23-29.

- Saari A, Virta LJ, Sankilampi U, Dunkel L, Saxen H (2015) Antibiotic exposure in infancy and risk of being overweight in the first 24 months of Pediatrics 135: 617-626.

- Alm B, Erdes L, Möllborg P, Pettersson R, Norvenius SG, et al. (2008) Neo- natal antibiotic treatment is a risk factor for early wheezing. Pediatrics 121: 697-702.

- Hoskin-Parr L, Teyhan A, Blocker A, Henderson AJ (2013) Antibiotic exposure in the first two years of life and development of asthma and other allergic diseases by 7.5 yr: a dose-dependent relationship. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 24: 762-771.

- Shaw SY, Blanchard JF, Bernstein CN (2010) Association between the use of antibiotics in the first year of life and pediatric inflammatory bowel Am J Gastroenterol 105: 2687-2692.

- McCracken GH Jr (1986) Aminoglycoside toxicity in infants and Am J Med 80: 172-178.

- Alexander VN, Northrup V, Bizzarro MJ (2011) Antibiotic exposure in the new- born intensive care unit and the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr 159: 392-397.

- Novitsky A, Tuttle D, Locke RG, Saiman L, Mackley A, et (2015) Prolonged early antibiotic use and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight infants. Am J Perinatol 32: 43-48.

- Cotten CM, Taylor S, Stoll B, Goldberg RN, Hansen NI, et al. (2009) Pro- longed duration of initial empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with in- creased rates of necrotizing enterocolitis and death for extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 123: 58-66.

- Cordero L, Ayers LW (2003) Duration of empiric antibiotics for suspected early-onset sepsis in extremely low birth weight infants. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 24: 662-666.

- Glasgow TS, Young PC, Wallin J, Kwok C, Stoddard G, et al. (2005) Associa- tion of intrapartum antibiotic exposure and late-onset serious bacterial infec- tions in infants. Pediatrics 116: 696-702.

- Polin RA (2012) Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-on-set bacterial sepsis. American Academy of Pediatrics 129: 1006-1015.

- Murphy K, Weiner J (2012) Use of leukocyte counts in evaluation of early-on-set neonatal sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 31: 16-19.

- Boghossian NS, Page GP, Bell EF, Stoll BJ, Murray JC, et (2013) Late-on- set sepsis in very low birth weight infants from singleton and multiple-gesta- tion births. J Pediatr 162: 1120-1124.

- Vermont Oxford Database (2015) Manual of operations for infants. Vermont Oxford Network. Burlington, Vermont, USA.

- Turcu R, Marsh TL, Patterson M, Khalife W, Omar S (2006) 46 Effect of An- tibiotics on Postnatal Intestinal Colonization in Term Newborns. Pediatr Res 60: 498-498.

- Jacquot A, Neveu D, Aujoulat F, Mercier G, Marchandin H, et al. (2011) Dy- namics and clinical evolution of bacterial gut microflora in extremely prema- ture patients. J Pediatr 158: 390-396.

- Johnson CL, Versalovic J (2012) The human microbiome and its potential importance to pediatrics. Pediatrics 129: 950-960.

- Kuppala VS, Meinzen-Derr J, Morrow AL, Schibler KR (2011) Prolonged initial empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with adverse outcomes in prema- ture infants. J Pediatr 159: 720-725.

- Grohskopf LA, Huskins WC, Sinkowitz-Cochran RL, Levine GL, Goldmann DA, et al. (2005) Use of antimicrobial agents in United States neonatal and pediatric intensive care patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24: 766-773.

- Baltimore RS (1998) Neonatal nosocomial infections. Semin Perinatol 22: 25-32.

- Stoll BJ, Temprosa M, Tyson JE, Papile LA, Wright LL, et al. (1999) Dexa- methasone therapy increases infection in very low birth weight infants. Pedi- atrics 104: 63-69.

- Beck-Sague CM, Azimi P, Fonseca SN, Baltimore RS, Powell DA, et al. (1994) Bloodstream infections in neonatal intensive care unit patients: results of a multicenter study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 13: 1110-1116.

- Sohn AH, Garrett DO, Sinkowitz-Cochran RL, Grohskopf LA, Levine GL, et (2001) Prevalence of nosocomial infections in neonatal intensive care unit patients: Results from the first national point-prevalence survey. J Pediatr 139: 821-827.

- https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Pages/Committee-on-Infectious-Diseases.aspx

- Sukumar M (2012) Need clarification on “abnormal labs”. Pediatrics 130: 1055-1057.

- Mukhopadhyay S, Eichenwald EC, Puopolo KM (2013) Neonatal early-onset sepsis evaluations among well-appearing infants: projected impact of chang- es in CDC GBS guidelines. J Perinatol 33: 198-205.

- Ellsbury DL, Clark RH, Ursprung R, Handler DL, Dodd ED, et al. (2016) A Multifaceted Approach to Improving Outcomes in the NICU: The Pediatrix 100 000 Babies Campaign. Pediatrics 137: 20150389.

Citation:Weiner J, Maranda L (2017) A Three Year Prospective Study to Safely Decrease Antibiotic Exposure in the Newborn. J Perina Ped 1: 004.

Copyright: © 2017 Weiner J. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.